At first, I was slow, very slow. I fatigued easily carrying patient charts from one end of the hall to the other. Patients lined in the hallway, waiting to be seen by the nurses would shoot puzzled glances at the woman walking down the hallway with a cane in one hand and patient charts in another. The walk down was exhausting and embarrassing. After two years, I still struggled with a new identity of being “disabled”. In between patient encounters, I would rest my legs and my hand. We were still paper charting in the beginning and of all things fatiguing, writing was my nemesis. The physical exams were done without hesitation or difficulty. I had mastered my own technique and by following a regimen of head to toe, I developed a routine. After my first day I felt invigorated, thoroughly satiated by the experience. The fatigue both mentally and physically, would rear its ugly head the next day. I realized soon that I would need to space my shifts to accommodate my disability. After a while, I realized that I could also ask for help with carrying charts or calling on patients. Often, counselors would help in these areas or patient techs and I began to rely on them. This greatly minimized fatigue and helped speed up patient flow.

Interestingly, patients too are helpful and empathetic. These patients are undergoing detoxification from substances ranging from alcohol, opiates, to benzos and despite their own struggles, they never cease to amaze me with their concern for my well-being. These are underserved and underestimated individuals, many of whom grew up in and out of prison, suffered exploitation, years of physical and sexual violence and yet, when they see me, they are concerned for my health. Curious, they will stop me in the hallway to ask about my disability and how it came to be. I distinctly remember earlier on, one particular patient, emaciated and weathered by years of battling a heroin addiction and poor nutrition, appearing far older than “their” 50 or so years of life who was genuinely concerned about me. Seated in the hallway seeking comfort in solace, as many patients do, “they” rose to their feet as I was passing by and gently grabbed my arm . “Honey, what happened to you? How come you have a cane?” Caught off-guard, I hesitated. How much I should share, I wondered. Should I even share? Eventually, I thought, maybe it will help “them” see that there are struggles we can overcome.

Unsure, I responded, “I had surgery for a brain tumor and became paralyzed. As you can see, I’m still recovering, but have come very far.”

“Honey, I’m going to pray for you. I’m so sorry, too young for that. God bless you. That’s amazing.”

I remember feeling stunned by this response as I was not expecting such kindness. If anything I thought it would satisfy “their” curiosity. A few others had gathered and also echoed their prayers and well wishes. I looked around at their sympathetic smiles, overwhelmed by their acknowledgement.

“I guess we’re all recovering from something” I said. I remember this statement striking a chord with them. I realized too the power of what I had just said. It was true, in life, we are all recovering from something. I stood there in the hallway with them for that brief moment not only as the clinician, but as a patient myself. One of my favorite quotes comes to mind as I often remember that moment, “Be kinder than necessary, for everyone you meet is fighting some kind of battle.”

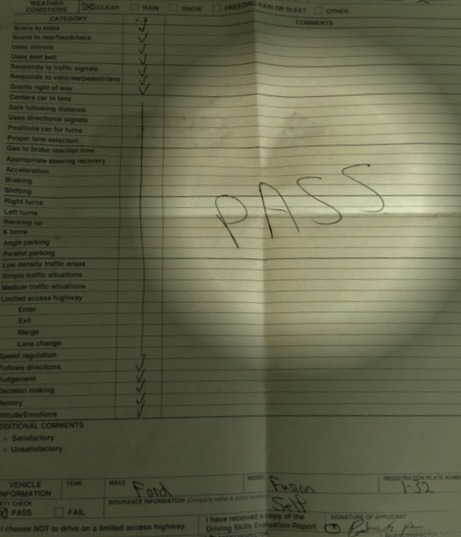

Since my return to clinical practice, I have successfully recertified my boards this fall and have been able to share my many patient care experiences with my students, in hopes that all the things I am blessed to have experienced can one day guide them into becoming more sympathetic and well-rounded clinicians. After practicing again, I feel validated teaching young aspiring PAs the values I hold dear in regards to patient care and also, I feel complete. For two years, something was missing, something which I only found upon returning to clinical practice. As I continue to grow in my profession, benefiting from the help and support of my colleagues, I make sure to remember to take each step down that hallway and in life, one step at a time or as we say in medicine, “all things in moderation”.